Working in a histology lab means that I get to see a lot of what our body looks like under the microscope. Quarterly I will share with you some of my photos from the microscopic world of our inner space and tell you a little bit about what we’re looking at.

As it is Cervical Health Awareness Month in the U.S., I have chosen to write about the cervix.

The cervix is the opening to the lower part of the uterus body. It averages at about 2.5-3 cm in length, and lies partly within the vagina. It is this part (the ectocervix) that can be easily viewed and examined during a cervical screen test.

As it is also Cervical Cancer Prevention Week in the UK during 20-26th January, we’ll see shortly which specific region of the cervix is of interest during this test and why. But, first of all, let’s see what the cervix does.

Functions of the cervix

♀ Monthly – it expands slightly to allow the flow of menstrual blood (this is thought to be the cause of period pains)

♀ As often as desired – the external os acts as the gateway for sperm to enter the uterus during their epic swim in search for an egg.

♀ Pregnancy – retains a protective “mucus plug” over its opening to help reduce the chance of bacterial infection transmitting into the uterus, and so helps to protect the developing baby. As labour draws near, the plug will eventually become thin, loosen and detach.

♀ Childbirth – whether it be naturally (through repeated uterine contractions) or induced, the cervix becomes thinner and the os becomes wider in preparation for the birth.

Cells of the cervix

Every organ and gland in our body is lined with one or another type of epithelial cell. The different types of epithelium each have their own function, and it is this function that determines where they can be found.

The cervix is lined with two different types of epithelium; the long, rectangular shaped columnar epithelium and the rounded, flat-ish squamous epithelium (non-keratinising squamous epithelium, to be precise). They do not appear mixed together as a random jumble of cells in a row, but rather the two types line different parts of the cervix that then converge at a particular region known as the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ).

Generally speaking, the majority of the ectocervix is lined with layers of squamous epithelium.

High power H&E showing the different layers of squamous cells in the cervix. From the basement membrane to the outermost layer that lies within the vagina, there are the youngest squamous cells in the basal layer, then (increasing in age) the parabasal, intermediate and the superficial layer.

As the squamous cells age and migrate their way through to the superficial layer, the nuclei become smaller and the cytoplasm increases. The cytoplasm also becomes clear (due to glycogenation, which is influenced by ovarian hormones) and, as a result, present as a honeycomb pattern.

Continuing inwards along the ectocervix, we eventually reach the opening of the cervix, the external os.

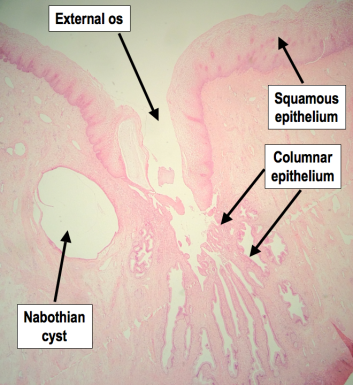

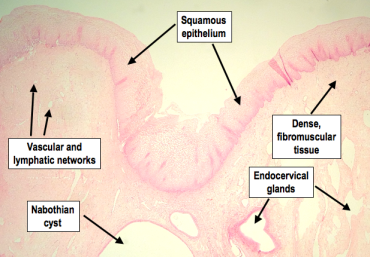

Low power H&E showing the squamous-lined ectocervix, the opening of the cervix (external os) and the columnar-lined endocervix. Columnar cells also line those gland-like structures you see in the lower right quadrant of the image.

Entering through this, to the endocervix and into the endocervical canal, the squamous cells come to an end at the squamocolumnar junction. It’s given that name because from here and on towards the internal os (see the first diagram), the cells which then come to line this region are columnar (glandular) epithelium.

High power H&E roughly showing the squamocolumnar junction, where the squamous and columnar epithelium meet.

The rows of columnar cells also become folded into gland-like structures. These, however, are not true glands.

Medium power H&E showing the columnar-lined endocervical “glands”. These are the same cells that line the endocervix.

The changing faces of the cervix

The location of both squamous and columnar epithelium throughout the cervix depends on the female’s age and hormones. Before she has her first period (premenarchal), the ectocervix is completely lined with squamous epithelium. Once puberty is underway, the rise in oestrogen levels cause the external os to open up, exposing the endocervical lining, which results in the ectocervix becoming lined with columnar cells. These newly exposed columnar cells (called an ectropian) eventually become replaced with squamous cells once again in a process known as squamous metaplasia. Some suggest this is triggered by the influence of oestrogen on the columnar cells together with their exposure to the acidity of the vagina, which the columnar cells are sensitive to.

The region in which the columnar cells are replaced with squamous cells is called the Transformation Zone. This zone also introduces a new SCJ, and here we see how (click to enlarge):

Interestingly, it is not thought that the columnar cells themselves change into squamous cells as the term “metaplasia” might suggest, but rather they become replaced by the increase in number of cells that go by the name of reserve cells. Another idea is that they become replaced by an ingrowth of squamous cells from the ectocervix. Either way, the early squamous cells that replace the columnar cells of the ectropian, although identified as squamous cells, don’t look like the conventional honeycomb squamous cells as seen in the young female’s ectocervix. The cytoplasm of these so-called metaplastic squamous cells stain up a lot darker with eosin, too. Here, see:

LEFT: Lower power H&E of the external os and endocervical canal. The boxed area shows a segment of transformation zone in the endocervical canal. Here, columnar cells have become replaced with squamous epithelium (squamous metaplasia).

RIGHT: On closer inspection, you can see the metaplastic squamous cells are distinguishable from the regular squamous cells of the cervix due to their darker staining cytoplasm and their lack of honeycomb appearance.

In older women, it is more common to find metaplastic squamous cells within the endocervix. This is because metaplasia starts from the original SCJ and works its way inwards towards the external os. As the metaplastic squamous cells age, the layers become thicker and the cells become glycogenated (clear cytoplasm), making them appear just like the original squamous epithelium. Therefore, the closer to the original SCJ, the more indistinguishable from the original squamous cells the metaplastic squamous cells become. Due to this, identifying the original SCJ can be very difficult, if not impossible. Some clues may be given, however, by the presence of Nabothian cysts, which always form within the transformation zone.

And so that’s the cervix.

Now onto that cervical screening test I mentioned….

Cervical Screening

Well, here’s how a sample of the cervical cells is taken:

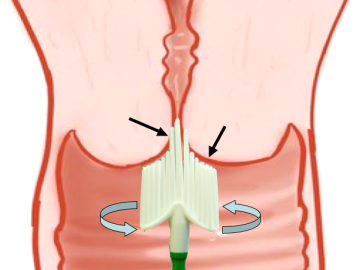

NOT TO SCALE. The longer bristles of the cervix-sampling brush are placed into the external os and rotated around to sweep and collect cells from both the ecto- and endo-cervix (arrows pointing to areas of contact).

The transformation zone is the most important region of the cervix to sample when screening for abnormalities. Almost all cervical cancers originate in the transformation zone, including adenocarcinomas. By referring back to the earlier diagrams that show where the transformation zones are, you will notice that the cervical sampling brush targets the exact areas of importance (please note the diagram is not to scale and the shorter bristles do cover more of the ectocervix in real practice).

It is thought that the reason why most cancers occur in the transformation zone is because the reserve cells that undergo metaplasia are very sensitive to cancer-causing agents such as the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can be transmitted through sexual contact. It is not surprising, therefore, that since metaplasia tends to occur during young age and the first pregnancy, that sexual activity and first pregnancy during early reproductive ages are high risk factors for developing cervical cancers.

To rule out the possibility of cancerous changes in the cervix, it is important that the length of the transformation zone is examined. In order to ensure this, an adequate cervical screen sample must contain both squamous and columnar epithelium.

Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is one of the most easily preventable cancers. This is because a cervical screening test can identify early changes to the cells, allowing us to monitor them and even treat them before they develop into cancer. Despite this, over 2,800 women the the UK were diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2010, and more than 930 women died from the disease.

Symptoms

Symptoms of cervical cancer are shared with other -but less sinister- conditions, and these symptoms include: offensive vaginal discharge, abdominal discomfort (particularly during sex), lower back pain and irregular bleeding between periods, after sex or after the menopause. It’s always important for the GP to investigate these symptoms, whatever the cause, and get them treated as soon as possible.

Preventing cervical cancer

Luckily, in the UK, all women aged between 25 and 60 are eligible for a free cervical screening test every 3 or 5 years, depending on their age. Cervical screening allows for the pre-cancerous warning signs to be caught early when they are much easier to treat. It’s a quick, simple and easy test that does save lives by preventing cancer from developing in the first place. It’s not the kind of test that ladies want to be putting off, really.

For more information on cervical screening, please do click:

All H&E photomicrograph images are Copyright © 2013 Della Thomas.

That is very informative Della. Thanks

Posted by Claudie | August 8, 2013, 8:44 pmThank you very much, Claudie.

Posted by Della | September 18, 2013, 5:29 pmHey Della. I would like to use one of your images in a paper. What research article is your second image derived from (portraying the different layers of the squamous cells in the cervix) so that I can accurately cite it?

Posted by Jen | September 18, 2013, 3:53 pmHi Jen,

Thanks for your comment. The photo you refer to is actually my own photo. Just out of interest, what context and for what kind of research article were you intending to use it for?

Thanks, Della.

Posted by Della | September 18, 2013, 5:27 pmHi Della, many thanks for writing such a wonderful account on cervical screening with very informative pictures. Can I please get your permission to use the first image on the female reproductive system in my PhD thesis? It will be duly acknowledged. Thank you!

Posted by Lila | January 27, 2014, 11:07 amHi Lila, thanks for your comment. Please can you email me via my contact button on my homepage?

I look forward to hearing from you soon.

Posted by Della | January 27, 2014, 10:25 pm